There was a reason Fannie Mae (Federal National Mortgage Association) and Freddy Mac (Federal Home loan Mortgage Corporation) were government created entities, before they became private corporations in the 1970s. They encouraged homeownership at a time when owning a home was only for the wealthiest. Though Fannie Mae -- the Federal National Mortgage Association -- was created in 1938 as part of the New Deal, it became important after WWII when the most basic 50 percent down payment was needed to finance a home purchase.

In fact, until the 1930s, residential mortgages in the United States were available only for a short term (typically five to 10 years) and featured "bullet" payments of principal at term. Unless borrowers could find means to refinance these loans when they came due, they would have to pay off the outstanding loan balance. In addition, most loans carried a variable rate of interest. Payments were prohibitively expensive for those just entering the middle class.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, Government-Sponsored Enterprises or GSEs, filled the void with 30-year fixed rate mortgages, loans that private banks thought too risky. Banks have always preferred short-term construction loans, or lines of credit that shortened their risk profiles.

And so the federal government created hybrid agencies that set up strict standards for so-called conventional, conforming mortgages. These were mortgages that conformed to stricter underwriting standards set up by Fannie and Freddie.

And now some in Congress want to abolish them altogether, and replace them with what is basically a privately-funded secondary market mechanism for packaging and selling guaranteed mortgages with sky-high capital requirements that will raise interest rates, putting even more consumers out of the housing market.

Firstly, the only problem with the GSEs in their current form was that they were under capitalized. And because they were under capitalized they suffered the same fate as all the under capitalized major banks bailed out by TARP funds. The only difference was that they were made wards of the government, which is what they were prior to the '70s, anyway. And they are now pouring $billions back into the US Treasury, some $203 billion to date since the recovery, when they were lent $188 billion.

So there is no reason to dissolve them and every reason to keep them as viable GSEs. This is mainly because their underwriting criteria have been the gold standard for borrower qualification, requiring income and asset verification, and assessing the likelihood this condition would continue, as we said.

That is why their default rates have about returned to historical levels, while so-called Private-Label mortgages -- those originated by banks that don't meet the stricter conforming standards -- have default rates still in the 6 percent rage, 3 times the Fannie/Freddie rate.

The latest proposal, by committee chairmen, Tim Johnson, a Democrat from South Dakota, and Mike Crapo of Idaho, the ranking Republican, have come up with a compromise that provides an explicit government guarantee for mortgages, but only after private investors have taken the first losses. The plan would set up a new federal regulator, called the Federal Mortgage Insurance Corporation, to provide the guarantee and regulate the system.

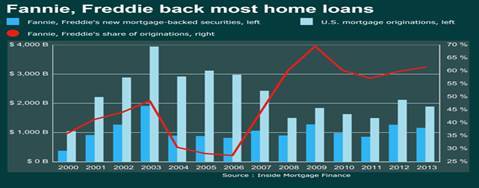

Having private investors take first losses, in lieu of Fannie and Freddie's stockholders, is a terrible idea because banks are much more risk averse, as we said. That's why Fannie and Freddie currently originate some 60 percent of all residential mortgages since the end of the Great Recession.

![2014-03-16-FannnieFreddie.jpg]()

Graph: WSJ/Inside Mortgage Finance

The new agreement would establish the Federal Mortgage Insurance Corporation as the insurer of last resort, but would require 10 percent private capital reserves, which is the rub. The guarantee, provided for a fee equivalent to 0.1 percent interest, would not kick in until the private reserves were wiped out. Fannie and Freddie would have remained solvent during the housing crisis if they had kept 4 percent of their capital in reserve.

The bill would create a single platform to standardize mortgage-backed securities, which are investment vehicles created by bundling mortgages and then selling off pieces of the bundle to spread the risk of default.

The bill would also set a minimum down payment of five percent, except for first-time home buyers, who would have to put down 3.5 percent for the mortgage to qualify for the guarantee. Some advocates have said they would prefer that the down payment amounts be left to the new regulator, who could adjust them in response to economic conditions.

The increased capital requirements and the government guarantee would raise the cost of borrowing for homeowners, said economist Mark Zandi, because the risks of the system would no longer be borne by all taxpayers. He estimated that interest rates would increase by 0.4 to 0.5 percentage points.

This would put Fannie/Freddie fixed rate conforming mortgages at or above five percent at rates that prevailed on the runup to the housing bust, when households hadn't lost so much income and accumulated record debts. That is not the case today, for most Americans, needless to say.

The bill could therefore eliminate the affordable housing goals that governed Fannie and Freddie, which required them to make a certain number of loans to people with low incomes but which some advocates said were easily gamed and worked to discourage lending in particularly expensive markets.

John Taylor, president and chief executive of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, said he had been assured that lenders would be encouraged to offer loans to low-income families through incentive pricing or would be required to do so by the regulator.

Really? It depends on the types of "encouragement" given to banks. They don't have public service goals unless required to, such as the Community Reinvest Act, that combatted red-lining, because lenders tended to avoid lending in lower-income neighborhoods. This is because they are required to maximize their profits, and affordable loans are by their nature very low profit margin entities.

So if not allowed to return as private corporations with stockholders bearing the risk, then at least keep them under some form of government control. There are many forms this can take, including strict regulations to protect their underwriting standards. There obviously has to be adequate capital, the lesson learned with commercial banks, but why reinvent the wheel when Fannie and Freddie have worked so well for millions of middle class homeowners?.

Harlan Green © 2014

In fact, until the 1930s, residential mortgages in the United States were available only for a short term (typically five to 10 years) and featured "bullet" payments of principal at term. Unless borrowers could find means to refinance these loans when they came due, they would have to pay off the outstanding loan balance. In addition, most loans carried a variable rate of interest. Payments were prohibitively expensive for those just entering the middle class.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, Government-Sponsored Enterprises or GSEs, filled the void with 30-year fixed rate mortgages, loans that private banks thought too risky. Banks have always preferred short-term construction loans, or lines of credit that shortened their risk profiles.

And so the federal government created hybrid agencies that set up strict standards for so-called conventional, conforming mortgages. These were mortgages that conformed to stricter underwriting standards set up by Fannie and Freddie.

And now some in Congress want to abolish them altogether, and replace them with what is basically a privately-funded secondary market mechanism for packaging and selling guaranteed mortgages with sky-high capital requirements that will raise interest rates, putting even more consumers out of the housing market.

Firstly, the only problem with the GSEs in their current form was that they were under capitalized. And because they were under capitalized they suffered the same fate as all the under capitalized major banks bailed out by TARP funds. The only difference was that they were made wards of the government, which is what they were prior to the '70s, anyway. And they are now pouring $billions back into the US Treasury, some $203 billion to date since the recovery, when they were lent $188 billion.

So there is no reason to dissolve them and every reason to keep them as viable GSEs. This is mainly because their underwriting criteria have been the gold standard for borrower qualification, requiring income and asset verification, and assessing the likelihood this condition would continue, as we said.

That is why their default rates have about returned to historical levels, while so-called Private-Label mortgages -- those originated by banks that don't meet the stricter conforming standards -- have default rates still in the 6 percent rage, 3 times the Fannie/Freddie rate.

The latest proposal, by committee chairmen, Tim Johnson, a Democrat from South Dakota, and Mike Crapo of Idaho, the ranking Republican, have come up with a compromise that provides an explicit government guarantee for mortgages, but only after private investors have taken the first losses. The plan would set up a new federal regulator, called the Federal Mortgage Insurance Corporation, to provide the guarantee and regulate the system.

Having private investors take first losses, in lieu of Fannie and Freddie's stockholders, is a terrible idea because banks are much more risk averse, as we said. That's why Fannie and Freddie currently originate some 60 percent of all residential mortgages since the end of the Great Recession.

The new agreement would establish the Federal Mortgage Insurance Corporation as the insurer of last resort, but would require 10 percent private capital reserves, which is the rub. The guarantee, provided for a fee equivalent to 0.1 percent interest, would not kick in until the private reserves were wiped out. Fannie and Freddie would have remained solvent during the housing crisis if they had kept 4 percent of their capital in reserve.

The bill would create a single platform to standardize mortgage-backed securities, which are investment vehicles created by bundling mortgages and then selling off pieces of the bundle to spread the risk of default.

The bill would also set a minimum down payment of five percent, except for first-time home buyers, who would have to put down 3.5 percent for the mortgage to qualify for the guarantee. Some advocates have said they would prefer that the down payment amounts be left to the new regulator, who could adjust them in response to economic conditions.

The increased capital requirements and the government guarantee would raise the cost of borrowing for homeowners, said economist Mark Zandi, because the risks of the system would no longer be borne by all taxpayers. He estimated that interest rates would increase by 0.4 to 0.5 percentage points.

This would put Fannie/Freddie fixed rate conforming mortgages at or above five percent at rates that prevailed on the runup to the housing bust, when households hadn't lost so much income and accumulated record debts. That is not the case today, for most Americans, needless to say.

The bill could therefore eliminate the affordable housing goals that governed Fannie and Freddie, which required them to make a certain number of loans to people with low incomes but which some advocates said were easily gamed and worked to discourage lending in particularly expensive markets.

John Taylor, president and chief executive of the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, said he had been assured that lenders would be encouraged to offer loans to low-income families through incentive pricing or would be required to do so by the regulator.

Really? It depends on the types of "encouragement" given to banks. They don't have public service goals unless required to, such as the Community Reinvest Act, that combatted red-lining, because lenders tended to avoid lending in lower-income neighborhoods. This is because they are required to maximize their profits, and affordable loans are by their nature very low profit margin entities.

So if not allowed to return as private corporations with stockholders bearing the risk, then at least keep them under some form of government control. There are many forms this can take, including strict regulations to protect their underwriting standards. There obviously has to be adequate capital, the lesson learned with commercial banks, but why reinvent the wheel when Fannie and Freddie have worked so well for millions of middle class homeowners?.