The Department of Health and Human Services recently delivered the latest enrollment numbers for the national and state health insurance marketplaces created by the Affordable Care Act. The main focus of the media has been the number of young people enrolling in the individual health insurance market.

The reason this has attracted so much attention is that if most of the enrollees are older and less healthy, they will generate high health care costs compared to the premiums they pay. That would make insurance premiums go up in the future, and coverage would become progressively less affordable.

If this older and sicker population is offset by a large number of younger and healthier enrollees, then costs and risks can be more easily managed. Younger and healthier people spend less on health care, and their premiums can be used to cover the expense of the higher-cost enrollees.

Originally, the White House hoped Americans between 18 and 34 would account for 35 to 40 percent of total enrollment by Jan. 1. The latest enrollment numbers show that about 24 percent of enrollment is in the 18-34 age range, while 30 percent enrollees are under age 35.

Opponents of the law were quick to say that the White House has fallen short and that premiums are sure to rise.

There are three reasons to question this assumption.

First, enrollment was affected by the problematic rollout of Healthcare.gov.

Second, the enrollment period is not over, and this snapshot does not represent what the final pool of enrollees is liable to look like. A better window for analyzing enrollment will come in April, after the first enrollment period ends.

Third, there is also little doubt that insurance companies will expand their marketing in 2014 and 2015 to focus even more on this younger population. That marketing campaign will clearly add to federal and state outreach efforts.

Finally, because the tax penalty for not purchasing insurance increases over time, more people are likely to buy insurance to avoid paying the penalty.

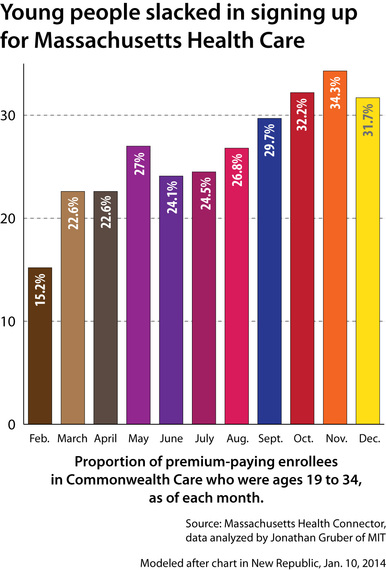

It is helpful to compare what is happening under the Affordable Care Act with Massachusetts' experience. Its state health care plan served as the model for the ACA.

![2014-01-23-ACAMassyoungenrollees.jpg]()

Massachusetts' very successful Health Insurance Connector (similar to the ACA exchanges), which began operation in 2006, had enrollment levels very similar to what the new marketplaces are seeing now. In its first three months of operation, the connector's enrollment levels for the 19-to-34 population did not exceed 22 percent. In fact, enrollment didn't reach its high of 34 percent until ten months after the Connector's startup.

There are other historical examples. In an April 2005 poll, only 21 percent of seniors had a favorable view of the Medicare Part D Drug prescription program. That program had a troubled rollout that fall, and a year later, 38 percent of seniors still thought that the program was not working well and required major changes or repeal.

As of 2013, 35 million seniors (roughly 76 percent of eligible seniors) are enrolled in the Part D program and it enjoys widespread popularity.

The Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was considered by many to be a failure because of its very low initial enrollment. Today, CHIP enrolls 90 percent of all eligible children.

The lesson here is that enrollment in these very large programs simply required time and education.

Premium increases are not guaranteed even if enrollment numbers for the young and healthy are lower than expected in the first year. Under the Affordable Care Act, several provisions are designed to protect insurance companies from losses if too many sick people enroll.

The first is a $10 billion reinsurance fund (covered by a $63 tax on all insurance plans), which covers much of the cost if a policyholder incurs medical bills that exceed $60,000 per year. The second provision, called "risk adjustment," redistributes premium money from health plans that paid out less to those plans that paid out more. The last provision, called a "risk corridor," limits insurers' potential losses and profits. All of these provisions are based upon the assumption that risk pools and enrollment will take some time to work themselves out.

Health care reform is a marathon and not a sprint. The initial results, while lower than hoped, are hardly a sign that that the Affordable Care Act is bound for failure. Nor can they necessarily be interpreted to say that success is inevitable. Reforming the individual health insurance market is dependent upon a number of provisions in the Affordable Care Act, as well as a great deal of work that has yet to be completed.

Insuring tens of millions of Americans without coverage will take time. As we've said before, we should be wary of instant analysis.

The reason this has attracted so much attention is that if most of the enrollees are older and less healthy, they will generate high health care costs compared to the premiums they pay. That would make insurance premiums go up in the future, and coverage would become progressively less affordable.

If this older and sicker population is offset by a large number of younger and healthier enrollees, then costs and risks can be more easily managed. Younger and healthier people spend less on health care, and their premiums can be used to cover the expense of the higher-cost enrollees.

Originally, the White House hoped Americans between 18 and 34 would account for 35 to 40 percent of total enrollment by Jan. 1. The latest enrollment numbers show that about 24 percent of enrollment is in the 18-34 age range, while 30 percent enrollees are under age 35.

Opponents of the law were quick to say that the White House has fallen short and that premiums are sure to rise.

There are three reasons to question this assumption.

First, enrollment was affected by the problematic rollout of Healthcare.gov.

Second, the enrollment period is not over, and this snapshot does not represent what the final pool of enrollees is liable to look like. A better window for analyzing enrollment will come in April, after the first enrollment period ends.

Third, there is also little doubt that insurance companies will expand their marketing in 2014 and 2015 to focus even more on this younger population. That marketing campaign will clearly add to federal and state outreach efforts.

Finally, because the tax penalty for not purchasing insurance increases over time, more people are likely to buy insurance to avoid paying the penalty.

It is helpful to compare what is happening under the Affordable Care Act with Massachusetts' experience. Its state health care plan served as the model for the ACA.

Massachusetts' very successful Health Insurance Connector (similar to the ACA exchanges), which began operation in 2006, had enrollment levels very similar to what the new marketplaces are seeing now. In its first three months of operation, the connector's enrollment levels for the 19-to-34 population did not exceed 22 percent. In fact, enrollment didn't reach its high of 34 percent until ten months after the Connector's startup.

There are other historical examples. In an April 2005 poll, only 21 percent of seniors had a favorable view of the Medicare Part D Drug prescription program. That program had a troubled rollout that fall, and a year later, 38 percent of seniors still thought that the program was not working well and required major changes or repeal.

As of 2013, 35 million seniors (roughly 76 percent of eligible seniors) are enrolled in the Part D program and it enjoys widespread popularity.

The Children's Health Insurance Program (CHIP) was considered by many to be a failure because of its very low initial enrollment. Today, CHIP enrolls 90 percent of all eligible children.

The lesson here is that enrollment in these very large programs simply required time and education.

Premium increases are not guaranteed even if enrollment numbers for the young and healthy are lower than expected in the first year. Under the Affordable Care Act, several provisions are designed to protect insurance companies from losses if too many sick people enroll.

The first is a $10 billion reinsurance fund (covered by a $63 tax on all insurance plans), which covers much of the cost if a policyholder incurs medical bills that exceed $60,000 per year. The second provision, called "risk adjustment," redistributes premium money from health plans that paid out less to those plans that paid out more. The last provision, called a "risk corridor," limits insurers' potential losses and profits. All of these provisions are based upon the assumption that risk pools and enrollment will take some time to work themselves out.

Health care reform is a marathon and not a sprint. The initial results, while lower than hoped, are hardly a sign that that the Affordable Care Act is bound for failure. Nor can they necessarily be interpreted to say that success is inevitable. Reforming the individual health insurance market is dependent upon a number of provisions in the Affordable Care Act, as well as a great deal of work that has yet to be completed.

Insuring tens of millions of Americans without coverage will take time. As we've said before, we should be wary of instant analysis.